BEBA unofficial debriefing

- BEhavioural BAsed forwarding

- Debriefing

- Future Work Perspectives

- The Rise of eBPF and SmartNICs

- April 2020: Moving Forwards

This post was left aside as a draft for a long time. Most of it was written in June 2018. Time has passed since the BEBA project has ended, but I really felt that some kind of debriefing was necessary on this blog.

After twenty-seven months of research, experiments, and proof-of-concepts, the BEBA project, set to improve capabilities and performances of programmable switches for SDN, has come to an end in March 2017. The results and outlooks for the project were presented a few months later to a jury from the European Commission.

As I am writing the first lines of this article, it has been nearly one year since we presented the results in front of the Commission. So far I had not taken the time to write a decent post about the end of the project (furthermore, I am no longer working at 6WIND). But having spent about two years on this project, I really wanted to throw together some notes about it. So, here we are: this is the unofficial debriefing of the BEBA project.

BEhavioural BAsed forwarding

I wrote an introduction about the project in a previous article. And as always, more details are available on the web page of the project. The idea behind BEBA was to design an interface offering stateful packet processing capabilities for programmable switches used in software-defined networks. The main problematics could be sum up as follows:

- How to design efficient stateful processing?

- How to design it in such a way that it can be used on programmable switches, without manual reconfiguration of the devices?

- How to validate the design, and make sure that it scales?

To answer them, six partners, from both the industrial (NEC, Thales Communication and Security, and of course 6WIND) and academic (CESNET, CNIT and KTH) worlds worked together, bringing along their experience in research, fast networking, hardware or software acceleration, open-source development, and many other fields.

The first answer to the stateful packet processing capability had emerged even before the project actually began. Initiated by researchers from the CNIT, the OpenState interface served as a basis on which most of the project was built. Instead of having just one forwarding table with actions associated to each flow, this interface would match packets against flow characteristics and flow state, and would then associate an action and a “next state” for the flow (for a longer description, please refer to my more detailed article linked above). As a result, the switch acts as a Mealy machine, and can successively apply various actions to the packets, depending on which state the flow currently has. It works, it is easy to implement. And it complies with the second problematic as well: control-plane protocols such as OpenFlow can be extended to support the specific set of commands needed to easily program the switches in this regard.

However, Mealy machines have one important restrictions: they are not efficient when it comes to implementing things like counter. If you were to count ten packets from a flow, for example, before changing the action on the packet, you need ten different states for that. Therefore, a more efficient processor was designed at a later time in the project: Open Packet Processor, somewhat more complex to understand, added a set of flow-specific and global variables, as well as a bloc that can perform arithmetic and logic operations on those variables, each time a flow is matched. This results in the implementation of a XFSM (eXtended Finite State Machine), which offers even more possibilities for stateful processing.

Debriefing

But is it fast? Does it scale? It scales vertically because both OpenState and Open Packet Processor were designed with OpenFlow compatibility in mind. Several of the proof-of-concept implementations realised for the project included not only the data plane API and the flow computing architecture, but also the integration with existing OpenFlow controllers. A complete work package (out of the six from the project) was dedicated to the design, the verification and the security evaluation of the control plane extensions created for those interfaces.

Regarding speed and overall performances, several proof-of-concept implementations have been developed and evaluated. Here are the most interesting ones. (Note: performance figures are only provided as a rough indication for performance: the objective was to get several proof-of-concepts, not competing implementations that should be put against one another. Measurements were done by distinct partners, on distinct test beds and architectures.)

-

A first software implementation based on the Ofsoftswitch software programmable switch, accelerated with the PFQ framework, by members of CNIT. Several improvements were brought to PFQ in this process: support for packet zero-copy, zero-malloc, better hash tables, batch processing of packets, etc. The netdev abstraction used to virtualise packets I/O (thus replacing Linux AF_PACKET sockets) was also improved (note that more recently, some work has happened in the same direction on Linux with AF_XDP—but this has nothing to do with PFQ). For 64-byte long packets, the throughput was drastically improved, to the point the final prototype is 96 times faster than the original Ofsoftswitch implementation! More than 14 million packets per second with four cores, against something like 150 thousand packets initially.

-

A second software implementation featured the mSwitch software switched based on the Netmap acceleration API, by NEC. mSwitch was eventually retained here after Open vSwitch was judged “too limiting” for obtaining a fast data plane. Netmap received several improvements through this work: prefetching, data structures shrinking, better encoding of the actions, single-cycle comparisons, etc. Performances were good as well: more than 8 million packets per second on one core.

-

For my part, I worked on a third software implementation of those interfaces, based on eBPF. And I made it work with the 6WINDGate product, based on DPDK, drawing benefits from the excellent acceleration it brings to packet processing on Linux. But it can also run natively on Linux, as an XDP program, without requiring any change to the system.

-

Last but not least, CESNET realised a hardware implementation based on NetFPGA. Part of the challenge on this work was to figure out how to best transmit the data: through the Straight Zero-copy Interface (SZE2), through the use of DPDK running on the host, or through a combination of the two, each solution having its own pros and cons. But this prototype was eventually able to process stateful flows at line rate on a 40 Gbps link.

The last prototype, in particular, was tested in a real networking environment, when it was deployed over (a duplicated version of) CESNET infrastructure, processing traffic at the scale of the whole Czech Republic country!

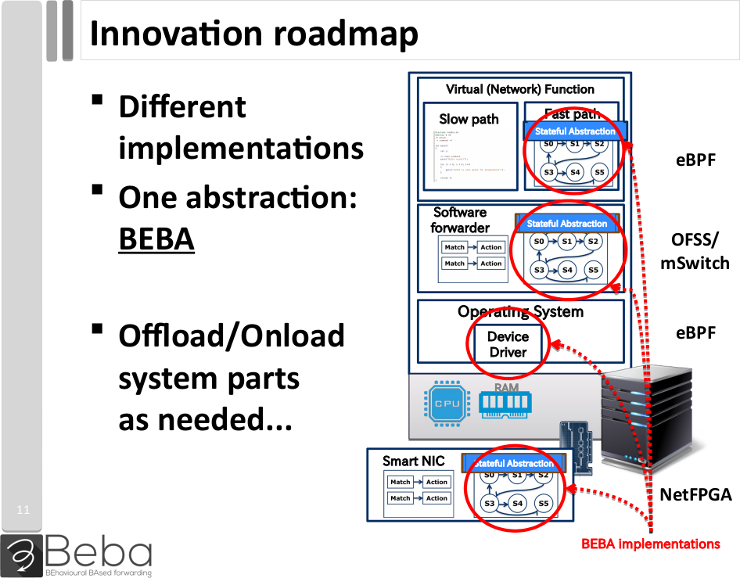

The variety of the prototypes show that the abstraction layer provided by the project can be implemented at various levels of the hardware and software stack, which makes it easy to port to a variety of systems. This was summarised on the following slide, presented to the jury from the European Commission during the final review.

Smart NICs mostly designates the FPGA-based implementations, but can also apply to multiprocessor “SmartNICs”. We will come back to that point later.

Overall, the performance results obtained over the multiple proof-of-concepts implementations are very encouraging, and make the interfaces developed for the BEBA project suitable for a variety of real world “middle-box” or “network-wide” applications: adaptive QoS, DDoS detection and mitigation, efficient ARP for data centres, and more (see also this post).

The project also led to the standardisation of the OpenState interface. Even if it did not keep the name, it was made part of the 1.6 revision of the OpenFlow standard.

Future Work Perspectives

Project BEBA is not the end of the journey, and there remains a lot to be done! The project introduced an efficient and versatile stateful programming abstraction. What now? Some of the leads mentioned during the review were the following:

-

More flexibility, possibly by trading a little bit of performance maybe to support more complex operations. This may involve additional functional blocks to support more advanced use cases.

-

Account for workload-specific properties: tailor the implementations to the use cases, for example to improve latency, or optimise memory usage, and so on. Find a way to automate that in order to bring some kind of “programmable programmability”.

-

Create truly programmable packet actions, by implementing something that gets closer and closer to a VLIW (Very Long Instruction Word) mini-processors for scalable and flexible packet modifications.

I know that the last item is the direction that researchers from the CNIT have taken to perform further experiments, and as far as I know there is still work in progress on that project.

The Rise of eBPF and SmartNICs

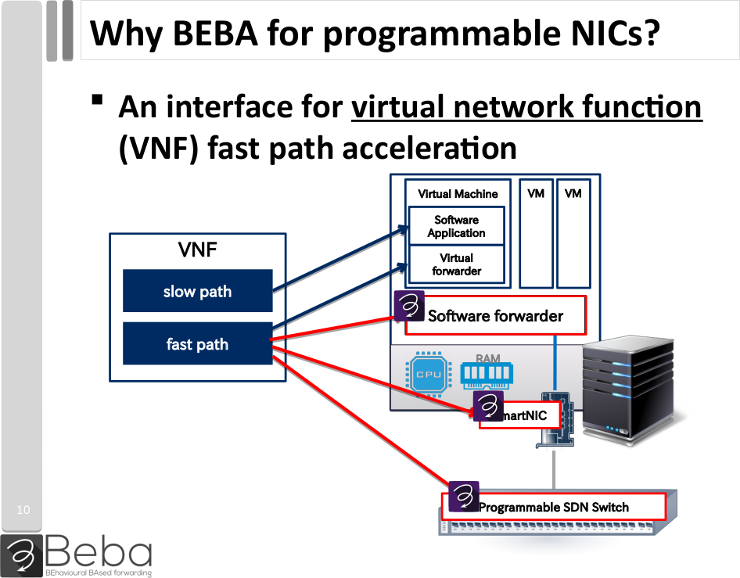

In that regard, it is interesting to see how the project comes close to the hardware, and relies on actions that could be accelerated by specific microprocessors. BEBA was implemented on FPGAs; but it could be also ported to multiprocessor SmartNICs. Such network devices embed a number of cores that can be programmed to implement the desired packet processing. Moving the processing to the network cards makes it simple to deploy a network functions to a variety of servers, possibly to all machines in a data centre, without having to worry about the system installed on the hosts. This possibility was discussed during the final review.

To do so we would need to implement it in the firmware of such a programmable NIC. Or we could also find a suitable interface. Some framework that can be used to implement OpenState, and that can be offloaded to the hardware… Sounds just like eBPF, doesn’t it? Hardware offload for eBPF on Netronome’s Agilio SmartNICs was at its beginning when BEBA finished, so there was no interaction whatsoever with those cards for the project. But it seemed like a natural continuation of what I did for BEBA, and this is one reason why I accepted a position at Netronome to start working on eBPF offload a few months after BEBA ended.

But besides my particular case, it is worth mentioning that although eBPF was initially a small aspect of BEBA, it works very well for implementing fast and stateful packet processing. At 6WIND we envisioned that from the beginning, and pushed to make this technology a part of the project. And today it is still growing fast. I am completing this article in 2020, three years after the end of BEBA, so I now have a glimpse of what was the future. eBPF is now used in a variety of project: Companies running data centres want to network functions, for example stateful firewalling or DDoS protection, for flexibility and better performance. Other firms are running eBPF on the host, to do load balancing or traffic monitoring at scale and with fewer constraints in terms of development (no kernel patch, no need to reboot, no stack on top of DPDK).

April 2020: Moving Forwards

People moved on but the achievements remain. The BEBA project gave birth to a powerful and efficient interface for stateful packet processing. It helped improve existing technologies and software. The various implementations made it to industrial products for several industrial partners, such as the FPGA-based NICs sold by Netcope (in tight collaboration with CESNET). Members from the academic world have been busy pursuing the acceleration of stateful processing. We do believe the project was a success, and that it helped improve network programming.

For my part I left 6WIND for Netronome, where I thoroughly enjoyed working on eBPF hardware offload, but I also realised one thing: SmartNICs are not the solution to everything. In particular, the industry has been shifting towards heavily virtualised environments, and many applications are now deployed as a set of microservices distributed over containers and virtual machines, managed through Open Stack or Kubernetes or similar solutions. Packets moving between those containers do not always need to go down to the interface, so are there ways to process them faster? Of course there are. Of course eBPF is one of them. A topic for a future project? I do not know, but I know that Cilium software, bringing networking and security to microservices environments, heavily relies on eBPF and does a fantastic job at it. So much that I joined them (at Isovalent) a few months ago, to work on the eBPF datapath.

BEBA gave me the chance to dive into eBPF, to get closer to SmartNICs, and of course to meet fantastic people. Everybody has moved on in their own direction, but we are all doing our best to improve network datapaths… Let’s see how far we can make it!

Whirl Offload

Whirl Offload